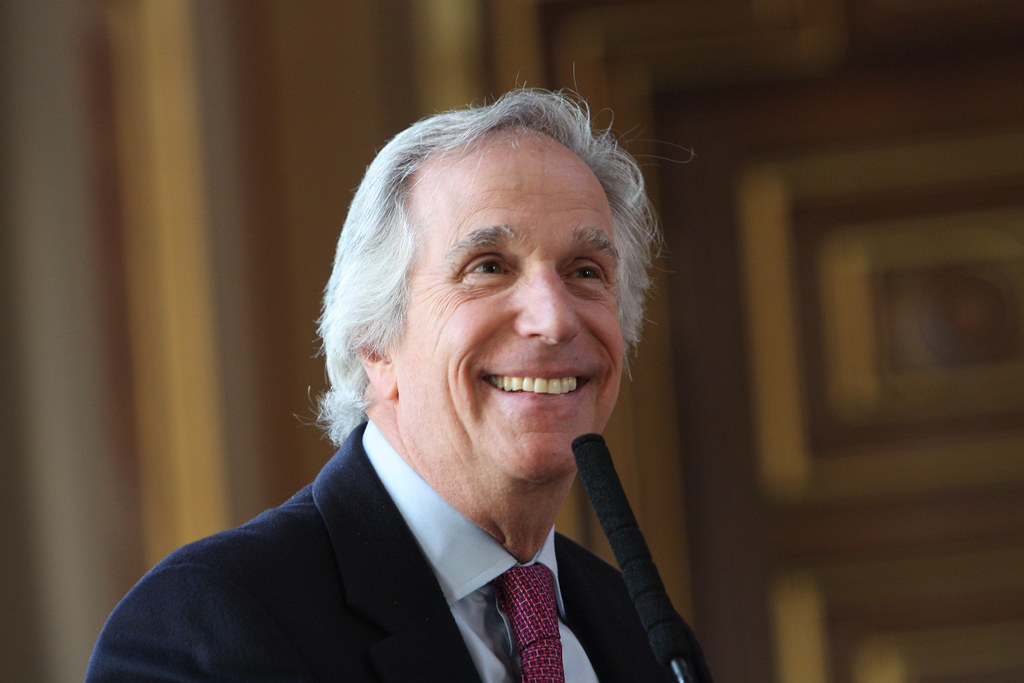

Henry Winkler is not interested in letting a good story about bad behavior go unchallenged, at least not when it involves people he loved working with. The longtime Happy Days star has been speaking out about the way Penny Marshall and Cindy Williams are remembered, pushing back on the idea that the Laverne & Shirley cast was some kind of backstage nightmare. Instead, he is painting a picture of a demanding, noisy, very 1970s sitcom set that still managed to be a place of deep friendship and serious work.

His comments land at a moment when classic TV is constantly being re-litigated through podcasts, memoirs, and social media clips. Rumors that once floated around studio lots are now treated like settled history, and Winkler is clearly uncomfortable watching Marshall and Williams get flattened into a single tabloid narrative. By revisiting how Laverne & Shirley spun out of Happy Days and what really happened on those adjoining soundstages, he is trying to restore some nuance to a show that was far more than its gossip.

The sitcom that became a cultural juggernaut

Before anyone argued about what went on behind the scenes, Laverne & Shirley was simply a hit. The series followed two Milwaukee roommates, Laverne DeFazio and Shirley Feeney, blue collar workers who turned factory shifts and apartment mishaps into broad, physical comedy. Across eight seasons, from its mid‑1970s launch through the early 1980s, the show became one of the defining sitcoms of its era, with its slapstick energy and working class setting standing out in a TV landscape that often leaned suburban and safe. Viewers tuned in weekly to watch the pair navigate dates, dead‑end jobs, and friendship fallouts, all while the opening theme and that “schlemiel, schlimazel” chant lodged itself into pop culture.

The scale of that success is easy to forget until you look back at how often Laverne & Shirley still surfaces in nostalgia cycles. The show’s run, which stretched across eight seasons starting on January 27, 1976, turned Penny Marshall and Cindy Williams into household names and cemented the characters of Laverne and Shirley as shorthand for ride‑or‑die friendship. That level of visibility is part of why any hint of trouble on the set has had such staying power. When a series becomes that big, the stories around it, fair or not, tend to grow just as large.

How Happy Days opened the door

Long before the spinoff, Henry Winkler was already a phenomenon as Arthur “Fonzie” Fonzarelli on Happy Days, and his character became the bridge that introduced Laverne and Shirley to audiences. The two women first appeared as dates for Fonzie and Richie Cunningham, crashing into the Happy Days universe with a chaotic energy that instantly clicked. That one appearance in 1975 was enough to convince executives that there was a whole series waiting to be built around these brash, funny women, and it is no accident that Winkler’s cool, leather‑jacketed persona helped sell the idea that they belonged in the same TV world.

Winkler has since talked about how his Fonzie character helped introduce Laverne and Shirley on Happy Days, describing how naturally they fit into that universe. In his telling, the trio worked together like “bread and butter,” a shorthand for how seamlessly Marshall and Williams slid into the show’s rhythm. That origin story matters, because it frames Laverne & Shirley not as an isolated production but as part of a larger Paramount Television ecosystem where casts and crews were constantly crossing paths on adjoining stages.

Rumors from the adjoining soundstages

Once Laverne & Shirley took off, the physical proximity between its set and Happy Days became part of Hollywood lore. The two shows filmed on neighboring soundstages on the Paramou lot, close enough that any raised voices could, in theory, drift through the walls. Over time, that geography fed a narrative that the Laverne & Shirley cast, and especially Penny Marshall and Cindy Williams, were locked in constant conflict, with their supposed fighting audible to their colleagues next door. It is the kind of detail that sticks in people’s minds, because it turns a vague idea of “tension” into something you can almost hear.

Those stories have been repeated so often that they now feel like accepted fact, including the claim that arguments between the co‑stars could be heard by the Happy Days cast from their adjoining soundstage on the Paramou lot. In some retellings, the noise is framed as proof that the production was out of control, a “nightmarish” environment where tempers constantly boiled over. That version of events has been especially sticky in fan conversations, where it is easier to picture a perpetually chaotic set than to imagine the more mundane reality of a long‑running show grinding through its weekly schedule.

Henry Winkler’s calm rebuttal

Henry Winkler has started to push back on that more sensational version of history, and his tone is notably measured. He is not pretending that Laverne & Shirley was a perfectly smooth operation, but he is very clear that the horror stories do not match what he saw. When asked about the rumors of “nightmarish behavior,” he has said that they are exaggerated and that the idea of a uniquely toxic set does not line up with his experience working alongside Marshall and Williams. Coming from someone who was physically present on those Paramou stages, that carries weight.

In recent comments, Winkler has refuted the idea that Penny Marshall and Cindy Williams were impossible to work with, stressing that any friction was part of the normal push and pull of a hit sitcom rather than evidence of a broken workplace. He has described how the two women could deliver a full scene in 20 minutes, three times in a row, a detail highlighted in a What To Know breakdown of his remarks. That kind of efficiency does not square with the idea of a set constantly derailed by personal drama, and Winkler leans on it to argue that the cast was far more professional than the gossip suggests.

What Marshall and Williams said about each other

Winkler is not the only one who has tried to complicate the “they hated each other” storyline. Over the years, Cindy Williams and Penny Marshall themselves have talked about their relationship, acknowledging that it was intense and sometimes difficult but also rooted in real affection. They have described each other as both collaborator and foil, the kind of partner who could drive you crazy in the morning and have you doubled over laughing by lunch. That duality is familiar to anyone who has ever worked closely with someone on a creative project that runs for years.

In one account, Cindy Williams and in a way that undercuts the idea of pure animosity. Williams has said that if she ever called Marshall one of the greatest friends of her life, Marshall would say the same thing back, and vice versa. That kind of language does not erase the disagreements, but it reframes them as part of a long, complicated friendship rather than a simple feud. Winkler’s defense slots neatly into that framing, suggesting that what outsiders heard as chaos was, from the inside, the sound of two strong personalities trying to make a hit show under pressure.

Normal friction versus “nightmare” myth

Part of what Winkler seems intent on doing is drawing a line between ordinary workplace friction and the kind of dysfunction that deserves the label “nightmare.” Sitcoms, especially in the multi‑camera era, were factories as much as they were creative spaces, with scripts being rewritten on the fly and actors asked to nail timing in front of live audiences. Under those conditions, raised voices and sharp exchanges are not exactly rare. By his account, that is what was happening on the Laverne & Shirley set, not some uniquely toxic meltdown.

In a video conversation, Winkler has said there were occasional disagreements on the Laverne & Shirley set but that these were typical of any production and not nearly as dramatic as some have suggested. He has emphasized that the stories of constant fighting are overstated, a point he made while addressing the rumors in a recent interview. That distinction matters, because it challenges the way fans and even some industry insiders have come to treat any sign of conflict as proof that a show was fundamentally broken. Winkler is arguing for a more realistic view, one where creative tension and professional respect can coexist.

How the rumors took on a life of their own

If the reality was more nuanced, the question becomes how the harsher narrative won out. Part of the answer lies in how stories travel once they leave the set. In the book Happier Days: Paramount Television’s Clas history, early accounts of the Laverne & Shirley production highlighted drama between Williams and Marshall, framing their clashes as emblematic of a show under strain. Those anecdotes, once printed, became source material for later retellings, each one sanding off context until all that remained was the idea of two stars who could not stand each other.

Winkler has pushed back on that framing, especially the suggestion that the early years of the show were defined by constant turmoil. In one recollection, he notes that there were Early rumors of drama between Williams and Marshall, but he has been blunt in saying, “No, that’s not true.” The fact that those rumors were preserved in a book about Paramount Television and its Clas era helped cement them as quasi‑official history. Winkler’s recent comments function as a kind of corrective footnote, reminding people that even well‑circulated stories can be incomplete or misleading.

Solo episodes, shifting dynamics, and lasting bonds

Another piece of context that often gets lost in the gossip is how the show itself evolved and how that affected relationships on set. As Laverne & Shirley went on, there were stretches where the focus tilted more heavily toward one character, with solo Laverne episodes that put Penny Marshall front and center. Any time a long‑running series shifts its balance like that, it can create tension, or at least the perception of it, especially when both leads started as equal partners. Those creative decisions, made in writers’ rooms and executive offices, often get retroactively folded into personal narratives about the stars.

Winkler has acknowledged that the solo Laverne episodes did not always sit comfortably with everyone, but he has also stressed that they did not erase the underlying friendship. He has recalled that despite the bumps, Marshall remained one of the greatest friends of his life, a sentiment echoed in coverage of the solo episodes and their impact. That kind of long‑term bond complicates the idea that the set was defined by bitterness. It suggests instead that the people involved were navigating shifting professional realities while still holding on to personal connections that lasted well beyond the final taping.

Why Winkler’s defense matters now

There is also a timing element to all of this. With Penny Marshall gone and Cindy Williams no longer around to tell her side in real time, the people who worked with them are increasingly the ones shaping how their careers are remembered. Henry Winkler, as someone who straddled both Happy Days and Laverne & Shirley, is in a unique position to do that. His decision to speak up against the harsher myths is not just about setting the record straight for trivia’s sake. It is about protecting the reputations of colleagues who are not here to push back themselves.

In a TV landscape where behind‑the‑scenes exposés can overshadow the shows they describe, Winkler’s more grounded account of the Laverne & Shirley set offers a reminder that not every loud story is a scandal. Sometimes it is just the sound of people working very hard, under bright lights, to make something that will still be talked about decades later. By insisting on that more balanced view, he is nudging fans to remember Marshall and Williams not as cautionary tales about “difficult” stars, but as the driving forces behind a show that, for all its off‑camera noise, delivered exactly what it promised on screen.

More from Vinyl and Velvet:

Leave a Reply