A new statewide smartphone ban for classrooms has moved from debate to reality, with the governor’s signature now locking in both the legal framework and the rollout schedule. The measure sets a clear implementation timeline that gives schools several semesters to shift policies, retrain staff, and communicate with families before enforcement fully kicks in. The law also lands at a moment when other states are racing to rein in student phone use, turning one state’s decision into a test case for the rest of the country.

Supporters frame the ban as a necessary reset for classrooms where social media, messaging apps like Snapchat, and constant notifications have become part of the daily background noise. Critics worry about student safety, parent communication, and uneven enforcement across districts. The way the timeline is structured, and how it aligns with similar efforts in other states and countries, will shape whether this new law becomes a model or a cautionary tale.

What the new smartphone ban actually does

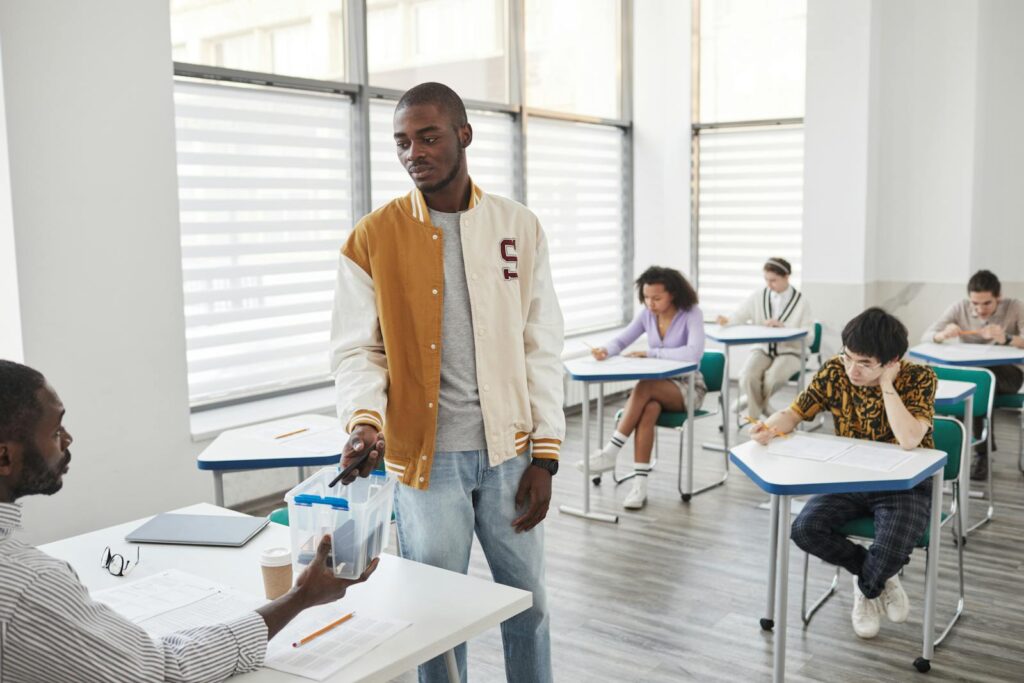

The newly signed law targets student smartphone use during instructional time, rather than attempting to regulate every minute of the school day. The statute directs local school districts to adopt policies that keep phones out of active classroom use, focusing on devices that support social media, messaging apps, streaming, and other nonacademic tools. In practice, students will be expected to keep phones off and out of reach during lessons, with teachers and administrators responsible for setting clear expectations and handling violations.

Reporting on the measure explains that the law tells school boards to limit smartphones in classrooms but does not create direct penalties for districts that fail to comply, leaving enforcement to local policy and public pressure. Coverage of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s decision to sign the classroom smartphone ban notes that the law applies across K-12 grades and is aimed at curbing access to apps such as Snapchat or other potential distractions during instructional time, while still allowing districts some flexibility in how they design their rules. That description of the statewide mandate and its classroom focus is grounded in the text of the bill and in summaries of the new law that highlight its emphasis on instructional time rather than blanket, round-the-clock prohibition.

Implementation timeline and key milestones

The most consequential feature for schools is the long runway built into the implementation schedule. Lawmakers structured the measure so that the new requirements apply beginning with the 2026-27 school year, giving district leaders more than a full planning cycle to design policies, negotiate with staff, and purchase any needed storage solutions such as locking pouches or classroom phone caddies. Legal analyses of the measure stress that school boards must adopt compliant policies ahead of that 2026-27 deadline, effectively turning the upcoming academic year into a transition period for piloting enforcement approaches.

One detailed breakdown of the statute explains that House Bill 4141 was signed after extensive debate over how quickly schools could realistically change their practices. That analysis notes that, on Tuesday in Feb, Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed House Bill 4141 into law and that the measure requires school boards to implement a policy limiting student use of smartphones in the school environment. A separate legal summary, also focused on the same legislation, points out that the law carves out an exemption for a “basic telephone,” defined as a phone used for voice calling that does not support internet browsing or the installation of applications, which will be important as districts draft their local rules.

How Michigan’s ban fits into a broader national and global shift

The new law arrives as Michigan and other states confront growing concern about how smartphones affect student focus, mental health, and school climate. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s signature on the classroom smartphone ban places the state among a growing list of jurisdictions where lawmakers and education leaders are moving from voluntary guidelines to binding rules. Reporting on her action notes that the law directs school districts to limit smartphone use during instructional time starting with the 2026-27 school year, and that it reflects pressure from teachers who say instruction has been diminished by constant digital distractions.

Nationally, the momentum behind school phone restrictions has accelerated. A survey of policy trends describes how districts across the country are locking away student cell phones in pouches or centralized storage to improve engagement. Another account of the political push notes that lawmakers in more than half of states are considering or have adopted some form of smartphone limits, arguing that bell-to-bell instruction is impossible when students can slip into TikTok or group chats at any moment. The Michigan law’s combination of a clear start date, local flexibility, and explicit focus on smartphones rather than all electronics mirrors many of these emerging models.

California’s parallel move and the 2026 convergence

While Michigan prepares for its 2026-27 rollout, California is on a similar track, creating a kind of de facto national benchmark year for school smartphone limits. Legislation signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom requires California’s 1,000 school districts, charter schools, and county education offices to adopt policies restricting or banning student smartphone use on campus by 2026. One overview of the law explains that every governing body must draft a policy, review it regularly, and update it every five years, embedding phone limits into the long-term governance of school climate.

Earlier coverage of the California debate describes how state legislators passed a bill on a Wednesday in Aug that directs districts to either ban or tightly restrict student smartphone use on K-12 campuses, with supporters citing research on attention, anxiety, and sleep issues in children. Another report on new laws affecting schools in Dec notes that The California Teachers Association and California Faculty Association have raised concerns that certain provisions could lead to censoring of student speech or limit access to information about sensitive issues, showing that even among educators there is no unanimous view of how far restrictions should go. A separate analysis of the same policy shift highlights that cellphone use is to be limited because of its link to mental health issues in children, reinforcing the shared rationale that connects California’s approach to Michigan’s new ban.

Classroom practice, exemptions, and unresolved tensions

On the ground, the success of the new law will depend less on statutory language and more on how schools translate it into daily routines. The Michigan statute’s focus on instructional time gives districts room to allow phones before and after school or at lunch, but many administrators are already considering stricter campuswide limits to avoid confusion. The exemption for a “basic telephone” means families who want their children to have a way to call home without access to Instagram or gaming apps may opt for flip phones or similar devices. Legal commentary that unpacks the law notes that, in Feb, the legislation defines these basic telephones as devices used for voice calling that do not support internet browsing or the installation of applications, which could spur a small but meaningful shift back toward simpler hardware for students.

Teachers and parents are also wrestling with edge cases and equity concerns. Some districts are exploring locked pouches that students keep with them, while others prefer centralized storage in homerooms or subject classrooms. Reports on Washington, D.C.’s policy, for example, describe how the district’s new rules target not just smartphones but a broader category of “personal electronic communication devices,” including smartwatches, Bluetooth headphones, and personal laptops or tablets, signaling that future iterations of Michigan’s rules might expand beyond phones. At the same time, civil liberties advocates and some educators in California, including The California Teachers Association and California Faculty Association, warn that poorly designed bans could interfere with student journalism, access to information, or the ability to document incidents on campus.

More from Vinyl and Velvet:

Leave a Reply