The Hillside Strangler murders have become shorthand for a particular kind of Los Angeles nightmare, a story of young women lured into cars and left on remote slopes. Lost in that history is the girl who says she slipped out of the killers’ grasp before the bodies began appearing, a teenager who insists she was almost their first victim. Her account, and the brutality that followed for others who were not as fortunate, shows how close the city came to confronting these men even earlier.

I trace her story alongside the verified record of the Hillside Strangler case, from the cousins’ early partnership to the women they exploited and the one famous daughter they spared. Her escape, and the way the killers moved on to other targets, exposes the gaps in protection for vulnerable girls and the chilling randomness that decided who lived and who died.

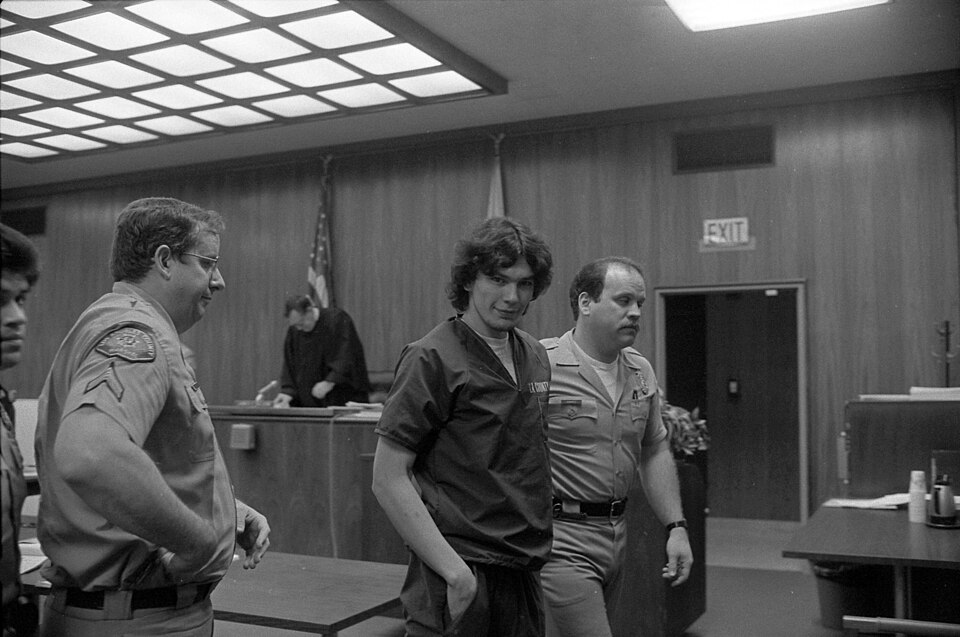

The cousins who became the Hillside Stranglers

The men later known as the Hillside Stranglers did not arrive in Los Angeles as anonymous drifters. They were family. In January, Kenneth Bianchi left Rochester, New York, and moved to Los Angeles, California, to live with his older cousin, a used-car upholsterer who already had a reputation for cruelty. That move brought together two men whose combination of manipulation, misogyny, and opportunism would soon terrorize the city’s hillsides.

Once Bianchi settled into his cousin’s orbit, the pair began testing how far they could push their control over women. They did not start with the staged “police” abductions that would later define the Hillside Strangler pattern. Instead, they experimented with more intimate forms of domination, using their home as a base and their family tie as a shield. The dynamic between the younger man from Rochester and the older relative in Los Angeles set the stage for a partnership that blurred the line between pimping, torture, and serial murder.

Sabra’s captivity inside Angelo Buono’s house

Before the first bodies were found on the slopes above Los Angeles, a teenage girl named Sabra was already living a private version of the nightmare. She was brought into the home of Angelo Buono and kept there as a captive, not a guest. According to later accounts, the girl was sometimes starved for days at a time, a deliberate tactic to break her will and keep her dependent on the man who controlled every aspect of her life. In that house, ordinary objects became instruments of confinement, and the promise of food or a brief outing became a leash.

Sabra’s treatment foreshadowed the violence that would later spill into public view. The same man who would be identified as one of the Hillside Stranglers was already practicing a pattern of domination that mixed sexual exploitation with calculated deprivation. The details of her captivity, preserved in records about Angelo Buono Jr., show that the cruelty did not begin with the first hillside body. It began in private rooms where a teenager was reduced to property.

The “outing” that turned into an escape

Sabra’s chance to get away came not through a carefully planned rescue but through a moment of carelessness by her captor. In early September, she was taken out of the house for what was described as an “outing,” a rare break from the locked rooms and hunger that had defined her days. For Buono, it was likely a test of how thoroughly he had broken her spirit, a way to see whether fear and dependence would keep her compliant even in public. For Sabra, it was the first glimpse of an exit.

When the opportunity appeared, she ran. That decision, made in seconds, separated her from the fate that would later befall so many other young women connected to the same men. Her escape during that outing did more than free one girl from a violent pimp. It may have interrupted an early stage of the pattern that would soon escalate into the Hillside Strangler murders, suggesting that the techniques used on Sabra were a rehearsal for the abductions and killings that followed on wooded hillsides across Los Angeles.

From hidden abuse to bodies on the hillsides

After Sabra slipped away, the violence did not stop. It shifted. The men who had honed their cruelty behind closed doors began targeting women whose disappearances would not immediately trigger alarm, including sex workers and runaways. They beat the girls, pimped them, raped them, and beat them even more when they tried to resist. They locked them in their rooms and treated them as disposable, a pattern that mirrored what Sabra had already endured but now involved multiple victims cycling through their control.

As their confidence grew, the cousins moved from private torture to public spectacle. Bodies started appearing on the wooded hillsides across Los Angeles, posed in ways that suggested both contempt and a desire to taunt investigators. The same men who had once confined a single teenager were now using the city’s geography as a dumping ground, turning isolated slopes into crime scenes. Accounts of how they treated the women under their control make clear that the murders were not a sudden escalation but the lethal extension of an existing pattern.

The near miss with a Hollywood legacy

Not every woman who crossed paths with the cousins ended up on a hillside. One of the most striking examples involves Catharine Lorre Baker, the daughter of Casablanca and M actor Peter Lorre. She accepted a ride from two men posing as authority figures, only to have the encounter take a sharp turn when they searched her handbag. Stunningly, they found identification that linked her to her famous father, a discovery that changed the tone of the interaction and, according to later accounts, may have saved her life.

The men who had already shown themselves willing to beat, rape, and kill women suddenly backed off when confronted with the name Peter Lorre. The implication is chilling. It suggests that celebrity, or at least proximity to it, could function as a kind of shield, even in the hands of men who otherwise treated women as disposable. The spared life of Catharine Lorre Baker stands in stark contrast to the anonymity of the victims whose bodies were left on the hillsides, and to Sabra, whose ordeal unfolded far from any spotlight.

How Sabra might have been their first intended murder victim

When I look at the sequence of events, Sabra’s story reads like a dry run for the killings that followed. She was a teenager under the total control of a man who would later be convicted as a serial killer, subjected to starvation, confinement, and psychological terror. The early September outing that gave her a chance to flee could just as easily have been the moment her captor decided to escalate from exploitation to murder, using a remote location to dispose of a girl no one seemed to be looking for.

Later, when Bianchi spoke to police about the pair’s activities, he described an intended victim who got away, a woman whose escape haunted the narrative of the Hillside Strangler case. In 1979, Bianchi told investigators that there had been a target who slipped through their grasp, a detail that aligns eerily with Sabra’s account of running during an outing. The idea that she was almost their first victim is not just a dramatic claim. It fits the pattern of experimentation and escalation that culminated in the hillside murders, and it echoes the way Bianchi later framed the one that got away.

The psychology of control behind the Hillside Strangler pattern

Sabra’s ordeal, the exploitation of sex workers, and the near miss with a Hollywood daughter all point to the same underlying psychology. The cousins were obsessed with control. They used hunger, threats, and impersonated authority to strip women of their autonomy, whether inside a locked room or on a dark street. The shift from pimping and beating to killing did not require a new mindset, only a decision that some victims were no longer useful alive.

In that light, Sabra’s escape becomes more than a lucky break. It is evidence that the killers’ sense of control was not absolute, that even a starved and isolated teenager could spot a crack in their routine and bolt through it. The fact that they responded by targeting other women, rather than retreating, shows how deeply rooted their need for domination was. They adapted their tactics, refined their impersonation of law enforcement, and chose victims who seemed less likely to fight back or be believed.

Why early warnings did not stop the killing

One of the most troubling aspects of Sabra’s story is how little it appears to have changed. A girl escaped from a man who starved and imprisoned her, yet the same man was able to continue abusing and exploiting women, eventually participating in a series of murders that gripped Los Angeles. That gap raises hard questions about how seriously authorities and communities took the accounts of vulnerable teenagers, especially those already entangled in prostitution or life on the margins.

If Sabra’s allegations had been fully investigated and acted upon, the pattern of violence might have been disrupted before bodies began appearing on the hillsides. Instead, the cousins were able to escalate, moving from hidden abuse to public killings while law enforcement struggled to connect the dots. The failure to translate early warning signs into decisive intervention is part of what makes her claim of being almost their first victim so haunting. It suggests that the line between survival and serial murder was not only thin, it was also ignored.

The legacy of the girl who got away

Today, when people talk about the Hillside Stranglers, they tend to focus on the official victim list and the courtroom drama that followed. Sabra’s name rarely appears in those conversations, even though her experience captures the beginning of the pattern and the possibility that it could have ended sooner. She represents the hidden tier of victims, the ones who survived but carried the trauma of captivity and the knowledge that others died in their place.

Her story, placed alongside the spared life of Catharine Lorre Baker and the women whose bodies were left on the hillsides, forces me to see the case not just as a sequence of murders but as a continuum of violence. At one end is a teenage girl starved in a house, at the other are the crime scenes that made headlines. In between are all the missed chances to intervene. Remembering the girl who escaped, and her belief that she was almost their first victim, is a way to confront those failures and to recognize that survival in cases like this is often a matter of timing, luck, and whether anyone listens when a frightened teenager runs for help.

More from Vinyl and Velvet:

Leave a Reply