From glowing watch dials to heroin-laced cough syrup, some of the strangest products in household history were once sold as wholesome essentials. Looking back at these seven old favorites shows how easily “miracle” goods slipped into everyday life, even when they were laced with cocaine, mercury, radium, asbestos, DDT, or lead.

1) Coca-Cola’s Medicinal Tonic Days

Coca-Cola began as a medicinal tonic, not a soft drink. In May of 1886, Doctor John Pemberton, a pharmacist in Atlanta, Georgia, created a syrup that blended coca leaf extract and kola nut, promoting it as a cure for headaches and fatigue. Earlier, one of the products he sold was called Pemberton’s French Wine Coca, a wine and coca extract mixture prescribed for nervous disorders, so the idea of a therapeutic pick-me-up was already central to his business.

By 1886, the new Coca-Cola formula was being marketed aggressively as a health tonic, and by 1903 it was reportedly selling more than 1,000 gallons per day in Atlanta soda fountains. As later histories of Coca-Cola’s early years note, customers embraced it as a modern remedy long before it became a global brand. The stakes were clear even then, because the drink normalized casual coca consumption in everyday households under the reassuring label of medicine.

2) Undark’s Glowing Radium Paint

Undark’s glowing radium paint turned ordinary household objects into eerie novelties. From 1918 to 1928, dial painters at the United States Radium Corporation in Orange, New Jersey, brushed this radium-laced paint onto watch and clock faces so they would glow in the dark on bedside tables and in kitchen drawers. The product was marketed as a modern convenience, and workers were even encouraged to lip-point their brushes, putting radioactive material directly into their mouths.

The women who did this work became known as the Radium Girls, and by 1930 more than 50 of them had died from radiation poisoning linked to Undark-coated dials. Their illnesses exposed how a supposedly harmless household glow could conceal lethal exposure. For families, the lesson was stark: the same luminous paint that made it easier to read the time at night also revealed how little consumers were told about the risks of cutting-edge chemistry.

3) Asbestos in Baby Powder

In the 1920s, Johnson & Johnson’s talcum powder was sold as a symbol of purity, dusted over infants and kept in bathroom cabinets as a daily staple. Yet internal records later showed that this “gentle” powder could contain up to 4 percent asbestos, a known carcinogen, in some batches. Documents from 1957 revealed that the company was aware of asbestos contamination in talc it used, even as the product continued to be marketed as safe for babies and mothers.

The powder remained a trusted nursery item into the 1970s, long after those internal warnings surfaced. For parents, the stakes could not have been higher, because the very product meant to protect delicate skin may have exposed families to microscopic asbestos fibers. The disconnect between the soft, reassuring branding and the hard mineral hazard illustrates how easily household care rituals can be built on incomplete or withheld safety information.

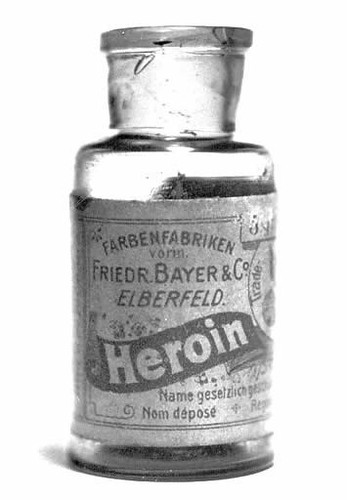

4) Bayer’s Heroin Cough Syrup

Bayer’s heroin cough syrup is one of the most startling examples of a pharmaceutical product sliding into home medicine cabinets. Introduced in 1898, the syrup contained diacetylmorphine, branded as Heroin, and was advertised as a non-addictive alternative to morphine for treating tuberculosis and pneumonia. At the time, heroin was believed to be a safer, modern pain and cough suppressant, and it was widely used in treating various respiratory conditions.

The product quickly became a commercial success, generating about $200,000 in sales in its first year, a huge sum for a new drug. As later accounts of how heroin was marketed explain, families were encouraged to keep it on hand like any other household remedy. The long-term consequence was that an opioid with powerful addictive potential was normalized as a routine treatment, foreshadowing later debates over how aggressively pharmaceutical companies promote painkillers.

5) Calomel’s Teething Powder Peril

Dr. Robert’s Teething Powder shows how even baby products could hide heavy metals. From 1847 into the 1930s, parents in the United Kingdom and the United States sprinkled this powder into infants’ mouths to soothe teething pain. Its active ingredient was calomel, or mercurous chloride, a mercury compound that was thought to calm fretful babies and reduce gum inflammation.

By the mid twentieth century, doctors linked calomel use in children to acrodynia, or pink disease, a debilitating condition marked by painful, discolored hands and feet. The United Kingdom government finally banned calomel-containing teething powders in 1948 after more than 1,000 cases were associated with the product. For families, the episode underscored how a trusted remedy, used in the most intimate caregiving moments, could quietly inflict long-term neurological and developmental harm.

6) DDT’s Household Insecticide Boom

DDT’s rise in the 1940s turned pest control into a symbol of modern domestic science. Promoted by the United States Department of Agriculture as a miracle insecticide, DDT was sprayed in kitchens, bedrooms, and backyards to kill flies and mosquitoes. Household brands such as Black Flag sold DDT aerosols that promised quick, odorless extermination, encouraging you to fog entire rooms as part of routine cleaning.

Production scaled rapidly, reaching about 125 million pounds annually in the United States by 1947 as farmers and homeowners embraced the chemical. Only later did evidence of environmental and health damage lead to a nationwide ban in 1972. The DDT boom showed how official endorsements could push a powerful toxin into everyday use, leaving families to grapple with residues in walls, furniture, and soil long after the marketing faded.

7) Lead Paint’s Durable Appeal

From 1900 to 1950, lead-based paints such as Dutch Boy White Lead were fixtures in American homes, prized for their bright color and durability. Manufacturers added lead to paint to increase gloss and longevity, and promotional materials like Dutch Boy’s Lead Party coloring book targeted children directly. Industry groups, including the Lead Industries Association, ran 1923 ads declaring that “lead is the life of paint,” framing the metal as a household ally rather than a hazard.

Advertising from the National Lead Company’s Dutch Boy campaigns even depicted painters “prescribing” pure lead for every room. By the 1970s, however, health authorities estimated that deteriorating lead paint had poisoned about 4 million children in the United States, causing learning problems and lifelong health issues. The story of lead paint captures how aggressively marketed “durability” can mask generational damage, especially in older housing where those coatings still cling to walls and trim.

More from Vinyl and Velvet:

Leave a Reply